On September 24, 2019, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced a the opening of a formal impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump. At the center of that inquiry lies an alleged effort by Trump to pressure the Ukrainian government into providing him with ammunition against one of his potential 2020 challengers, Joe Biden.

In fact, both #RussiaGate and #UkraineGate, as well as the Kremlin’s support for Trump during the 2016 election, have their roots in the 2014 Ukraine Crisis, which froze over US-Russian relations and led Washington to impose costly sanctions on Russia. In other words, the developments currently threatening to cripple the Trump administration are international in character and closely connected to dynamics we examine in Exit from Hegemony—especially contestation over international order and related competition for the allegiance of weaker states.

Plenty of long-term causes contributed to the 2014 Ukraine crisis, but its proximate origins can be found in a tussle between two geo-economic projects, one led by Russia and the other by the European Union (EU).

In the period before the crisis, the EU was, as part of its Eastern Partnership Initiative, negotiating a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with Ukraine. The successful conclusion of the DCFTA would have given Ukraine greater access to the European market and meant its adoption of many EU standards. At the same time, Russian President Vladimir Putin pushed for Ukraine’s inclusion in a competing Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)—an emerging regional organization aimed at promoting Russian-led economic integration among post-Soviet states.

President Yanukovych indicated an initial willingness to sign the EU agreement. The Kremlin, for its part, began to raise concerns about the DCFTA in 2013 but did not, according to EU diplomats, voice major objections during routine consultations. This led many to neglect warning signs, including Armenia’s decision, under Russian pressure, to choose the EAEU over a DCFTA earlier that year.

As negotiations continued, Moscow increased pressure on Kyiv to abandon the DCFTA process. Russian President Putin used a number of carrots and sticks, including an offer of discounted Russian gas and to purchase up to $10 billion of Ukrainian government bonds. On November 21, 2013 Ukrainian President Yanukovych announced that his government would not agree to a DCFTA, prompting demonstrators to gather in Maidan square in the capital of Kyiv. The protests soon became directed at the regime itself. They triggered a series of events that culminated in Yanukovych fleeing the country in February of 2014. In response, Russia invaded and annexed Crimea. It then deployed well-rehearsed tactics in support of separatists in Ukraine’s eastern provinces.

The Ukraine crisis also accelerated Russian efforts to shore up membership in and support for the EAUA. Moscow secured Armenian and Kyrgyz entry in 2015, thereby expanding the EAUA to a total of five states.

Today, many Western commentators continue to view the EAUA as a Russian-dominated and ineffective organization—and to caution against Western recognition or engagement. But the organization has weathered its initial growing pains, including Moscow’s lack of consultation with other member-states over imposing counter-sanctions on EU goods. The EAUA is boosting its global profile by negotiating trade agreements with states outside of the post-Soviet region, including Serbia, Egypt and Singapore.

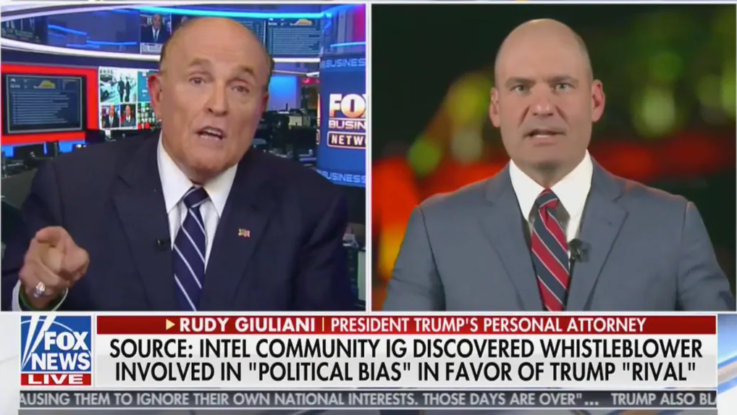

Here’s where the connections shift from straightforward to strange. Not long ago, the Washington Post confirmed that Trump’s private lawyer Rudy Giuliani—himself a key player in #UkraineGate and international hired gun—was planning to make a paid appearance at a conference in Armenia “sponsored by Russia and the Moscow-based Eurasian Economic Union”. He was scheduled to speak on the same panel—on EAEU “Export-import Opportunities—as Sergei Glazyev, a western-sanctioned Kremlin insider and advisor to Putin.

Following the initial Washington Post report, Giuliani indicated that he would no longer attend the conference, claiming “I didn’t know Putin was going.” The Post noted that “Giuliani’s decision to take part in the conference astounded national security experts.”

Guliani’s own past participation in similar forums, as well as his initial willingness to attend this year’s conference, highlights that:

- The EAEU continues to seek external partnerships and recognition in a bid to compete with established Western economic organizations like the EU; and

- Its organizers saw Giuliani as an important ‘node’ within the Trump administration, as well as a potential ally in weakening American opposition to the EAEU’s development.

Why pay Guliani to speak on a topic that he knows nothing about? The answer is to normalize the EAEU’s activities (“its just a conference!”) while deepening the Kremlin’s own transnational ties within the West. As we discuss in the book, this reflects a broader effort—ranging from the National Rifle Association to the Lega in Italy—to achieve through money and favors what Moscow cannot through force of arms.