The last two years has seen a fierce debate about the very idea of “liberal international order.” Patrick Porter—who has a book on the subject coming out—and Paul Staniland have each written blistering criticisms. Graham Allison called it a “myth” in Foreign Affairs. A number of scholars have, of course, pushed back. Rebecca Friedman Lissner and Maria Rapp-Hopper wrote a directly reply to Allison that is definitely worth reading, as did Michael Mazarr. I even wrote a blogpost or two on the subject at Lawyers, Guns and Money.

We have plenty to say about this debate in Exit from Hegemony. One of the pieces that we give a “shout out” to in the text is Rohan Mukherjee’s “Two Cheers for Liberal Order,” which appears in the H-Diplo/ISSF Policy Series (yeah, I know, the name of the outlet doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue).

It’s a short piece, so I recommend just reading it. He makes some important points, such as that “critiques that focus on the order’s adverse consequences are essentially arguing that it was not uniformly liberal, international, rules-based, etc. This is an unrealistic expectation of any set of institutional arrangements that is designed to stabilize international relations.” He also points out that “liberal order” doesn’t mean “good” or “benign”, yet critics sometimes offer criticisms of the dark side of liberal ordering as refutations of the very concept.

We largely agree with Mukherjee, and we also point out that there’s an important distinction between the American hegemonic system—the parts of the globe that the United States unequivocally “manages” via its hegemonic infrastructure—and broader global order. Both are facing challenges, and sometimes from the same sources. But over the last few decades the United States has often taken the lead in challenging liberal order and, as Mukherjee points, found itself constrained by that very order.

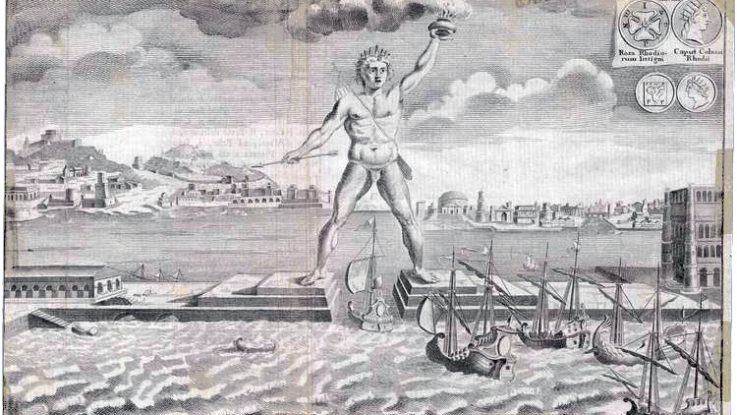

In Exit, we push Mukherjee’s argument a bit further. Critics compare the realities of international order (and the U.S. hegemonic system) to an idealized conception of liberal international order. Yes, when your baseline is the hyperbole of American leaders or the imagination of philosophers, contemporary international order doesn’t look very liberal. But when compared to, say, the Soviet system, the order imposed on Europe by the Nazis, Ming China, or the Roman Empire? It looks pretty darn liberal.