Ishaan Tharoor has a very good discussion of the broader context of Trump’s meeting with Polish President Andrzej Duda.

Though accustomed to lectures from Brussels, Duda and his allies are hoping for a boost ahead of a June 28 presidential election. He faces a tougher-than-expected challenge from the opposition. Some polls show that he could lose to Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski if this weekend’s vote yields a July runoff. “Emphasizing strong relations with Washington is particularly crucial for Duda, given Poland’s growing isolation within Europe as his government has become increasingly autocratic,” my colleagues reported. “The European Union has censured Poland for failing to uphold democracy, rule of law and fundamental rights, and has said his government’s judicial revisions threaten the independence of the courts.”

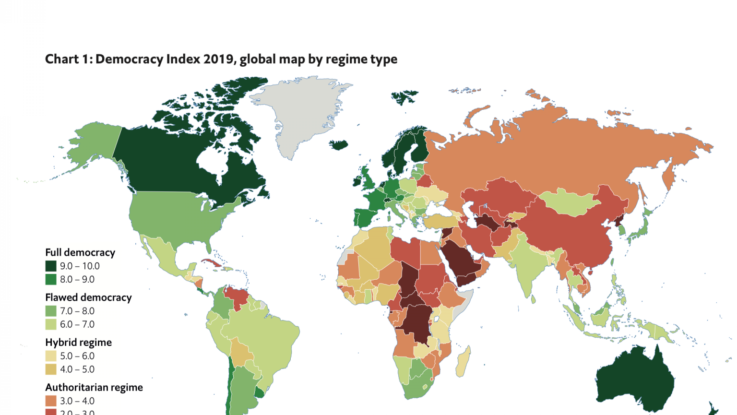

That doesn’t appear to pose much of a problem for Trump, who has found common cause with a global menagerie of illiberal nationalists over the past three years. Trump and his political allies see in central Europe an emerging nationalist vanguard in countries such as Poland and Hungary. And Duda could present the White House with an opportunity to launch another shot across the bow toward liberal Europe: The two presidents are expected to finalize the details of a number of defense deals, which include discussions over the possibility of U.S. troop deployments in Poland.

Duda’s arrival comes in the wake of Trump’s decision to withdraw about a third of U.S. forces stationed in Germany, a decision prompted both by Trump’s factually challenged insistence that Germany is “delinquent” in payments to NATO, as well as his personal antipathy toward German Chancellor Angela Merkel. The announced withdrawals from Germany set off alarm bells in Congress, where both Democrats and Republicans have issued stern statements warning Trump against undermining the United States’ position in Europe.

“We would like an increase in American forces in Poland,” a person close to Duda told the Guardian. “We aren’t happy that America is withdrawing forces from Germany, we want as many U.S. forces in Europe as possible, but it’s a separate issue, the more forces we have in Poland, the better.”

This gets at one of my enduring frustrations with the nominally progressive personalities who, since 2016, have consistently minimized the threat Trump poses to liberal democratic governance. Even if they were right about the U.S. domestic context – which they most assuredly are not* – they almost completely ignore the international effects of having a reactionary nationalist in charge of the U.S. government.

To some degree, this is understandable. When you look at a lot of dimensions of U.S. foreign policy – ranging from the Iraq War to bipartisan support for authoritarian regimes in countries like Saudi Arabia – it might seem ridiculous to say that the contemporary United States can be a force for liberal democracy.

But this overlooks the myriad “small” ways that U.S. diplomacy advances human rights and democratic norms. As a consequence, it misses the downside risks of Washington not only ending those practices, but also actively putting its thumb on the scale for illiberal parties and movements.

In this respect, it’s interesting that Pew’s most recent survey of overseas attitudes towards the United States finds that Trump is views much more favorably by supporters of far-right parties than by the overall population, even though he’s still generally under fifty percent with those subgroups.

If Biden wins in 2020, his administration is going to have to make some very difficult choices about how it handles reactionary and illiberal parties in countries allied with the United States. If you believe, as I do, that we’re potentially in the 1920s v. 2.0, then Washington will need to consider how to manage an environment where its key allies include left, center-left, and center-right parties within other countries.

During the Cold War, the U.S. was perfectly okay meddling in the affairs of other democracies in ways that should be completely off limits. We obviously don’t want that. At the same time, Russia’s happy to sow division – and support the far right – in liberal democracies. As we’ve learned in the United States, it can be hard to deal with that when major political players see that meddling as a feature rather than a bug. So, given this asymmetric toolkit, we’re looking at a very difficult time.

*I must say that I think my critique of the anti-anti-Trump argument that he’s not a serious threat to democracy ad the rule of law has held up pretty well.