Many discussions about the end of “liberal international order” play out in extremely stylized (one might even say “crude”) terms. Some treat liberal ordering as an all-or-nothing deal, in which the only alternatives are a “rules-based order” or realpolitik, unconstrained great-power conflict. Those who treat American leadership as essential to international liberal order sometimes adopt this rhetoric—even if some of the same analysts elsewhere stress that other liberal democracies may be able to substitute for the United States.

Liberal order is not all or nothing; we do not face a future that either takes the form of “rules-based order” or “the law of the jungle.” There have been many different forms of liberal ordering over the past two hundred years.

In Exit from Hegemony we distinguish between three major components of liberal order.

- Political liberal governance: “The architecture of international orders is politically liberal to the extent that it establishes the responsibility for governments to protect some minimal set of individual rights for their citizens, with more liberal orders favoring developed liberal-democratic governance among their members.”

- Economic liberalism, which “refers to the belief in, and commitment to, encouraging open economic exchange and flows among states.”

- Liberal intergovernmentalism “concerns the means, or form, of international order.” It “favors… multilateral treaties and agreements, international organizations, and institutions that make rules and norms; monitor compliance with those rules and norms; resolve disputes; and provide for public, private, and club goods.” It “also manifests in bilateral agreements and institutions that reflect principles of juridical sovereign equality even when concluded by states that are significantly unequal in their power relations.”

In both principle and practice, there are lots of different kinds of liberalism within these baskets and many different overall configurations of the three components. For example, intergovernmentalism was much less important to the practice of nineteenth-century British liberal ordering—which rested heavily on empire and imperialism—than to the practice of American ordering after 1945.

To get a sense of variation within these components, consider post-war economic liberalism.

The immediate post-World War II economic order was characterized by “embedded liberalism”. States committed to liberalizing trade by defending a system of capital controls designed to shield individual economies from destabilizing financial flows and shocks…. In the wake of the Soviet collapse, neoliberalism becomes institutionalized in the so-called Washington Consensus of championing free trade—including establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2000—and financial liberalization… Indeed, the unwavering commitment to rules-based economic globalization in the 1990s and 2000s created a “democratic trilemma” for states, as governments are increasingly constrained in their domestic monetary and fiscal policies by adherence to international economic commitments, the threat of capital flight, and potentially punishing financial crises.

International order can be disaggregated in other ways. In a new piece in International Security, Alistair Iain Johnston notes that international orders involve multiple domains. As he writes:

[T]his exercise yields a world of multiple orders in different domains (e.g., military, human rights, trade, the environment, and information), rather than a single, U.S.- dominated liberal order. Some of these orders are internally contested, and some are in tension with others. The empirical evidence across these different orders, presented in an admittedly broad-brush way, suggests that China is not challenging the so-called liberal international order as much as many people think.

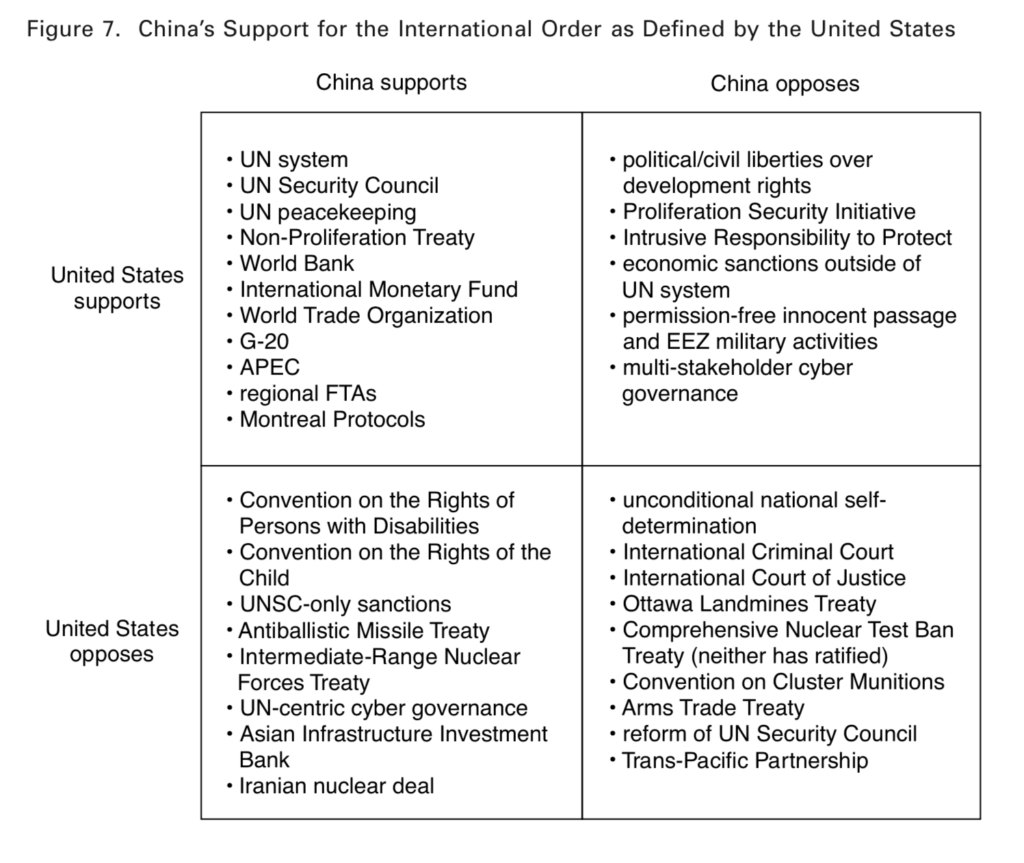

Johnston argues that such an approach reveals a more nuanced picture of Chinese (and, for that matter, American) positions on international order. He illustrates this with a fairly granular catalog of domains.

This level of specificity is highly instructive, but if we take a more holistic picture, our sense is that, first, China is generally supportive of liberal intergovernmentalism but opposed to many dimensions of political liberalism and, second, like any other great power, China’s approaches to order are conditioned by power-political concerns.

As we discuss in Chapter 4, Beijing has both pursued multilateral engagement and also developed a range of new multilateral institutions. On the one hand, Beijing seeks to expand its influence by constructing alternative institutions where it enjoys a much greater say. On the other hand, it does so by increasing its diplomatic leverage in more venerable institutions, such as the United Nations. Just like the United States and other great powers, China seeks to influence other country’s votes and positions through carrots and sticks, such as offering development assistance or threatening to withhold market access.

What Johnston calls “constitutive order” is, in practice, similar to what we call “liberal intergovernmentalism,” especially when it comes to the sovereign equality of states and principles of non-interference. In our view, the general thrust of China’s approach to order is to maintain intergovernmentalism, as well as various forms of economic liberalism, while trying to strip out many dimensions of political liberalism that raise legitimacy problems for its authoritarian government. Russia is generally onboard with this project, although Moscow also would like to see a recognition of its “privileged sphere of influence,” which amounts to a decidedly illiberal way of organizing relations among sovereign states.

Overall, this suggests a future marked by stronger liberal ordering in some domains, such as intergovernmentalism, and contention and decline in other domains, such as democratic norms and rights.

But this is not the end of the story. It’s easy to focus on two major sources of mutations in international order: rising—or, in the case of Russia, less “rising” than “muscle flexing”—authoritarian great powers and the policies of the Trump administration. It’s a bit harder to zero in on endogenous sources of transformation, such as the ways in which uneven liberal ordering has feedback effects on the character of international order.

A good example of this appears in a new New York Times story by Selam Gebrekidan, Matt Apuzzo and Benjamin Novak, entitled “The Money Farmers: How Oligarchs and Populists Milk the E.U. for Millions.” As they explain:

Every year, the 28-country bloc pays out $65 billion in farm subsidies intended to support farmers around the Continent and keep rural communities alive. But across Hungary and much of Central and Eastern Europe, the bulk goes to a connected and powerful few. The prime minister of the Czech Republic collected tens of millions of dollars in subsidies just last year. Subsidies have underwritten Mafia-style land grabs in Slovakia and Bulgaria.

Europe’s farm program, a system that was instrumental in forming the European Union, is now being exploited by the same antidemocratic forces that threaten the bloc from within. This is because governments in Central and Eastern Europe, several led by populists, have wide latitude in how the subsidies, funded by taxpayers across Europe, are distributed — even as the entire system is shrouded in secrecy.

In essence, the European Union, one of the central forces for liberal ordering in the 1990s and 2000s, is entrenching and empowering many of the regimes that are pushing illiberal democracy within the EU. The significance of EU subsidies (and not just in agriculture) becomes even clearer once we recognize how control over patronage networks is one of the key mechanisms by which illiberal democrats maintain power.

As we examine in the book, and Alex Cooley discusses in his Security Studies article that deals with similar themes, this is one aspect of a more general story: one of liberal hubris that spreading some elements of liberal governance and open trade would create positive feedback effects that would, in turn, “lock in” liberal democracy.

But regardless of the ideological wagers behind these developments, they also highlight another trajectory of how liberal order has been, and is, evolving. Here it is useful to think about how much of Trump’s farm bailout is flowing to large agribusinesses and the already wealthy. While not quite the story of EU farm subsidies, the US bailout is part of a general trend toward government policies enriching the powerful, who in turn use their wealth to further skew the political economy in their favor. Rinse and repeat.

I’ve blogged about the nexus between liberal order and global kleptocracy before. But it bears repeating that at the intersection of domestic economic policy and liberal economic order is a configuration—involving capital mobility and rent-seeking by the powerful—that may push the texture of liberal order increasingly in the direction of one favoring oligarchy and kleptocracy. As we discuss in Chapter 8, which concerns possible future orders:

A striking feature of the liberal international order is how relatively easy it is for authoritarian elites, kleptocrats, and oligarchs to use its institutions, rules, and organs for illiberal purposes, most notably the laundering of their money and their reputations on a global scale. In retrospect, the push for expansion of the global liberal economic architecture and the creation of a number of institutions and supporting services designed to facilitate financial liberalization proceeded without adequate safeguards. It gave birth to an transnational infrastructure built to facilitate grand corruption on an unprecedented global scale.

Here, the Trump administration is both symptom and accelerant. Trump, Jared Kushner, and their inner circle are creatures of transnational oligarchy and kleptocracy; the policies of the administration, some of which, of course, are bog-standard Republican priorities, certainly seem to reflect that. As Casey Michel argues;

But this is just the most recent example of Trump purposefully treating corruption precisely backwards. Documents from early 2019 show that the Trump administration “sought repeatedly to cut foreign aid programs tasked with combating corruption in Ukraine and elsewhere overseas,” as the Washington Post reported. All told, the anti-corruption funds earmarked for Ukraine that the White House attempted to gouge out of the budget stretched into the hundreds of millions of dollars. One agency targeted for a direct hit to their coffers: Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau, Kyiv’s foremost anti-corruption body.

The effort to degrade America’s ability to corral corrupt actors goes all the way back to the early days of the administration. In addition to hacking off requirements that American oil companies disclose what they’re funneling to kleptocratic parasites elsewhere, the Trump administration announced in late 2017 that it was pulling the U.S. out of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), the leading pro-transparency energy consortium in the world. As one anti-corruption voice noted at the time, this was only the “latest in a series of actions in Washington that have damaged the country’s credibility as a proponent” of “honest dealings globally.” Departing the EITI followed Trump’s announcement that the U.S.’s Foreign Corrupt Practices Act—the keystone of America’s anti-corruption policies; the rock upon which America’s anti-corruption legacy was built—was a “horrible law.” According to former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Trump repeated these complaints directly from the Oval Office.

What this makes clear, we hope, is that disaggregating liberal international order reveals that some of its elements are more robust than others, but that isn’t necessarily a good thing. Some combinations of liberal ordering are downright alarming. We ignore evidence of trends in their direction at our peril.