Back in 2017, Dani Nedal and I wrote an article about Donald Trump’s claim that “unpredictability” is a good approach to conducting U.S. foreign policy. We looked closely at the logic behind it, and the analogy drawn by some pundits to the Nixon “madman theory” of coercive diplomacy. We found both lacking.

Thus, for the United States, unpredictability carries enormous risks. That’s true for Nixonian calculated irrationality, too, but much more so for Trumpian unpredictability. Rivals and allies can easily interpret mixed signals from different voices in the administration and frequent high-profile policy reversals as evidence that the president does not mean what he says, that he has no idea what he is doing, or that he can change his mind on a whim. Intentionally fostering uncertainty reduces the credibility of existing commitments.

Unraveling the American alliance network by undermining confidence in Washington is probably the worst way to implement an America First policy. It undercuts a major source of American strength without gaining the benefits that might follow from strategic retrenchment — that is, of making deliberate decisions about what commitments are key to American security and which can be shed, while taking steps to ensure that unwinding those commitments don’t harm vital interests and alliances

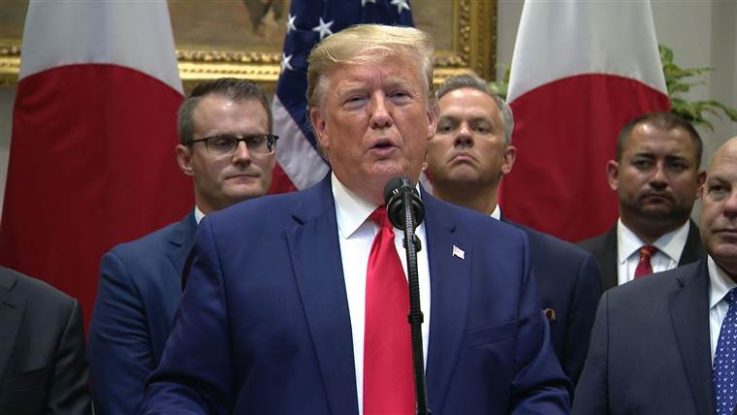

I’ve been thinking of this article today in the context of Trump’s sudden decision to abandon America’s Syrian Kurdish allies in the face of a Turkish offensive. Trump’s erratic foreign-policy behavior—which continued with a particularly strange tweet warning Turkey of economic obliteration—has, according to the New York Times, thrown “Middle East policy into turmoil… with a series of conflicting signals after his vow to withdraw American forces from the region touched off an uprising among congressional Republicans and protests by America’s allies.”

Meanwhile, Mark Bowden has a must-read article in the Atlantic detailing Trump’s chaotic foreign-policy process.

“If the president says ‘Fire and brimstone’ and then two weeks later says ‘This is my best friend,’ that’s not necessarily bad—but it’s bad if the rest of the relevant people in the government responsible for executing the strategy aren’t aware that that’s the strategy,” the general said. Having a process to figure out the sequences of steps is essential. “The process tells the president what he should say. When I was working with Obama and Bush,” he continued, “before we took action, we would understand what that action was going to be, we’d have done a Q&A on how we think the international community is going to respond to that action, and we would have discussed how we’d deal with that response.”

To operate outside of an organized process, as Trump tends to, is to reel from crisis to rapprochement to crisis, generating little more than noise. This haphazard approach could lead somewhere good—but it could just as easily start a very big fire.

Trump isn’t causing the erosion of American leadership, but he sure seems intent on accelerating it.